Running cadence (or stride rate) is a vital part of efficient running technique. Not only is it linked to improved efficiency and performance, but also reduced injury risk.

So what is it, and why does it matter?

In this article we look at the science of running cadence, and how it affects injury risk, and efficiency. We then look at training approaches to improve your cadence, stride length and running speed.

What is running cadence?

From a sports perspective, cadence provides a measure of the rate or rhythm of a movement. When running, it provides a measure of your stride rate, or number of steps you take per minute (spm).

This can vary significantly between different runners. It also depends on running speed (as a rule cadence should increase as running speed increases).

Is there an optimal cadence for running?

If you’ve been running for a while, then no doubt you’ve heard reference to 180spm being the optimal cadence range.

But is that really the case? Should you be aiming to run at 180spm?

The quick answer to this is… no! 180 is not a magic cadence that will make you a faster runner.

The truth is: every runner has their own “individual” optimal cadence range – essentially a cadence range where there is greater efficiency and reduced risk of injury.

With cadence there are two very important points to consider…

- First, there is no magic cadence value that is optimal for every runner (we’re all different)

- Second, you have your own optimal range which will change depending on running speed

How does pace affect cadence?

For most runners, cadence increases inline with speed. Similarly, we would expect stride length to increase inline with running speed.

Why is cadence important?

While there are many factors that affect running performance, at its simplest, there are only two metrics that ultimately determine running speed:

- Stride length

- Cadence

It’s an unbreakable law of running that running speed is always determined by stride length multiplied by cadence.

Clearly, cadence is a key part of the running speed formula – but that’s not all…

Three benefits of optimal cadence:

- Faster running pace

- Improved efficiency

- Reduced over-striding and lower injury risk

As we’ve seen, running pace is determined by a combination cadence and stride length.

However, this varies significantly between runners:

- Some runners make use of a faster cadence and shorter stride length,

- Others have a slower stride rate and longer stride.

Here’s the thing: if you really want to maximise running performance, you need to develop the conditioning to maintain a fast cadence and a good stride length.

Before taking a closer look at cadence, let’s quickly look at how to measure it – feel free to skip this part.

How to measure cadence?

The simplest approach is to use a gps watch capable of recording cadence. There’s also a variety of footpods (Stryd footpod, Garmin, Zwift RunPod, Polar etc) that provide greater accuracy along with several other metrics.

Another option is to count the number of steps you take during one minute of running.

One point to note: it’s a lot easier to do this by just counting the steps taken on one leg, and then multiplying that figure by 2. Alternatively, count the steps on one leg for 30 seconds and multiply this by 4.

Cadence and injury risk

Increasing cadence can be very effective for reducing the injury risk associated with over-striding.

What is over-striding?

Over-striding is where your feet land, or strike the ground, too far in front of your centre of mass.

So, why is this a problem? When this happens, it creates a slight braking effect, which can have several negative effects:

- First, it reduces efficiency by increasing ground contact time – the time your feet spend in contact with the ground

- Second, it disrupts your natural running rhythm.

- Third, it increases injury risk – especially when you land too far in front of the centre of mass, with an extended knee.

So how can you reduce over-striding?

One approach is to focus on technical aspects of running form, so that your foot lands under, or nearer to, your centre of mass.

However, improving technique can be a difficult and slow process. It requires regular feedback and monitoring, and a lot of conscious effort. That said, most runners will see improvement with consistent, purposeful training.

A quicker approach is to work on increasing your running cadence, particularly when this is low we’ll come to this shortly.

Run cadence and over-striding

If you over-stride, then increasing cadence can be beneficial.

Research shows that runners can reduce vertical oscillation, ground contact time and reduce the breaking impulse by increasing their cadence (1).

Does a low stride rate mean you are over-striding?

Is a low cadence always bad? While low stride rates are linked to over-striding, a low cadence doesn’t always mean that you’re over-striding. It has to be considered in relation to running speed.

As an example, my cadence varies depending on running pace:

- If I run at 2:45/km it can be over 210spm,

- At 3:20/km it’s ~185-190spm,

- Then at 4:00/km it’s ~175-180spm,

- At 5:00/km it’s ~165-170spm,

- And if I was to run at 6:00/km, it might be as low as 160-165spm.

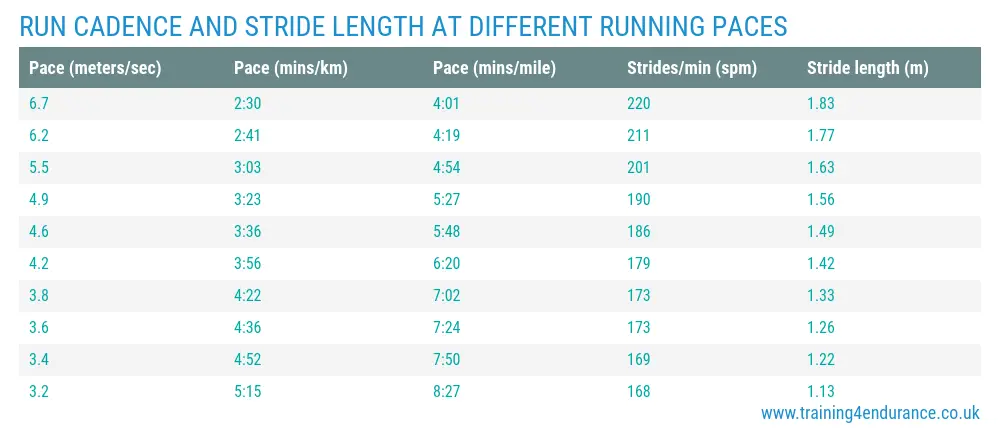

In each case, I’m not over-striding, my stride rate and length naturally adjust to match my running pace. The data below shows how this changes as pace increases.

Here, stride frequency and length are dynamic and increase as pace increases.

How to increase cadence and reduce injuries

Research has shown that increasing your cadence by ~5-10% can help to reduce overstriding, reduce loading of the hip and knee joints and potentially reduce injury rates (1, 6).

Here’s a simple approach you can use to increase it:

- Start by gradually increasing cadence over a period of weeks.

- To do this, start by increasing stride rate by ~3-5% during your easy/moderate pace runs (ideally twice per week). You might find this easier if you do this for short intervals during your run. As an example, you could alternate between 3-5minutes run at 3-5% higher cadence, and 3-5minutes at your normal stride rate.

- As this gets easier, increase the length of these intervals, until you can maintain this throughout the run.

- If you’re still overstriding, try increasing stride rate by a further 3-5%.

- One point to note here: don’t make too many changes and seek advice if you’re unsure.

Remember, that cadence should increase as pace increases, so you may need to increase this at faster speeds as well.

Cadence and running efficiency

Research has shown there is a link between stride frequency and running efficiency (2-5). For this reason, increasing run cadence has gained attention as a way to improve running efficiency.

So, will this make you a quicker and more efficient runner?

This really depends on “your” optimal cadence, and also your training experience.

What determines your optimal stride rate?

This is determined by several factors including height, limb length, aerobic fitness, muscular endurance, percentage of slow twitch muscle fibres, training history, flexibility (specifically in the hips) as well as stability in the knees and core strength.

Let’s not forget that stride length also influences stride frequency. Some runners naturally have a longer stride. And their optimum cadence may be lower than runners with a shorter stride length.

Research looking at cadence and efficiency

Research looking at runners preferred vs optimal cadence…

Optimal cadence is affected by training experience

- Inexperienced runners used a cadence that was below optimal, and by increasing this they can improve running efficiency (3).

- In contrast, trained runners were much closer to optimal (4): trained runners cadence was ~3spm lower than optimal vs ~6spm lower in novice runners.

Optimal stride rate varies for each runner

One important point here: there is wide individual variation between runners (3).

With this in mind, just increasing your cadence to a one size fits all range (such as 170-180spm) is not the best approach.

For most runners, this won’t significantly improve efficiency and may be detrimental. It’s also worth considering your level of conditioning – if you’re in the ‘well-trained’ category, then you’re more likely to already be near your optimal range.

So, while cadence can influence efficiency, it’s important to first know what your “optimum” cadence is. It’s also important to remember this will be different for different running speeds.

Finding your optimal cadence

To find the optimal range, researchers (3) measured runners’ heart rates across a range of cadences and speeds. Each run comprised 3 minutes at a set cadence, followed by 2.5minutes of walking. From this, researchers could identify the athlete’s optimal range.

How did they do this?… the process was straightforward: they simply identified the cadence with the lowest heart rate.

To test this yourself follow this simple formula:

- Run at your preferred cadence for 3minutes – this should be at a submaximal speed (ideally below threshold/tempo intensity).

- Rest for 2-3minutes, then repeat at the same speed across a range of cadences. As an example, you could test this at 2-3% and 5-6%, below and above your preferred cadence.

- The cadence with the lowest heart rate shows greater efficiency.

Important note: your optimum cadence will probably be different across different running speeds. It may also change as your running fitness changes.

Another consideration is cardiac drift. This is where heart rate continues to rise even when intensity, or pace, is kept the same. Cardiac drift has a greater effect as intensity increases, making this test less effective at faster speeds.

Cadence and running speed

Will increasing cadence make you a faster runner? In short, if cadence naturally increases because your running fitness improves, then you will run faster. However, just increasing your stride rate is unlikely to make you significantly faster.

Running fitness must also improve

The simple truth is: running pace is always determined by a combination of cadence and stride length. And both are affected by your current running fitness and conditioning level.

To achieve the fast cadences and long stride lengths seen in elite runners, takes many years of specific training.

While most runners cannot maintain such a high cadence and long stride length during sustained running; interval training improves your ability to sustain these for short intervals. And overtime you will develop the conditioning to sustain these for increasingly longer periods.

This is one of the reasons why interval training is so beneficial for endurance running performance.

Using intervals to improve run cadence and stride length

So why use intervals?… The real advantage here is: they train you to run with a faster cadence and longer stride length.

Contrast this with using a fast cadence at slower running speeds – such as always running at 180spm, whatever the running speed. Here, it has the opposite effect.

A combination of fast cadence + slow running speed = significantly shorter stride length! While that might benefit stride rate, it won’t benefit stride length.

Simply making yourself run at a faster cadence, during all of your runs is not the answer.

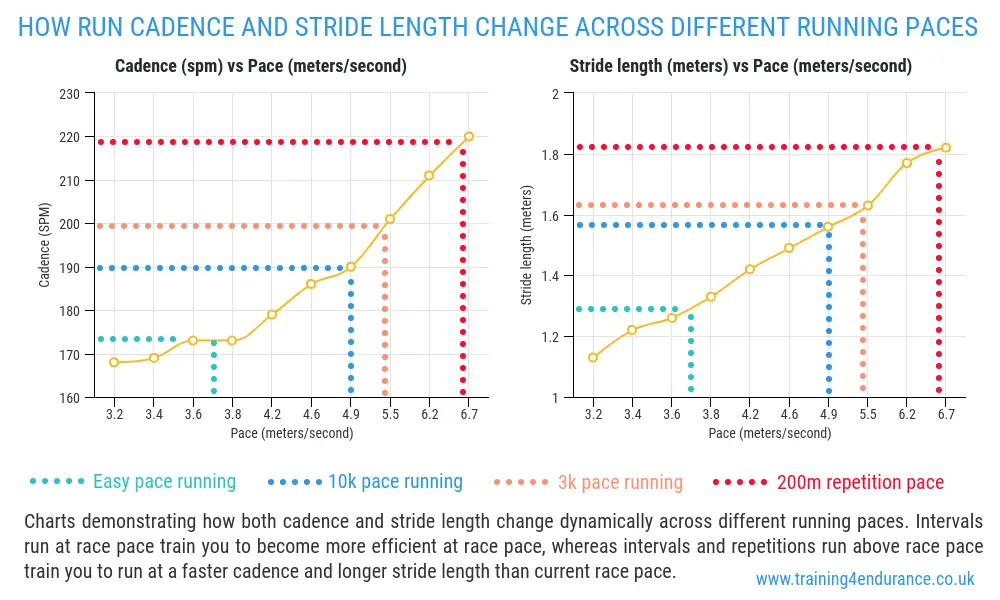

The charts below really illustrate how in my case, both run cadence and stride length increase significantly as pace increases.

You can see from the chart, faster running intervals (in this case 3k pace and 200m repetitions) were a very effective way to lift cadence and stride length. And while race pace Intervals (in this case 10k pace intervals) were less effective, they do improve running efficiency at the ‘specific’ cadence and stride length used when racing.

For this reason, I prefer not to focus on deliberately running at a specific cadence. Instead, I train in ways that push the upper limits of both cadence and stride length.

So don’t focus on hitting a specific cadence. Instead, include key training sessions that develop cadence and stride length – such as faster intervals and hill sessions. As a result, you will achieve consistent and progressive improvements, that will directly transfer to improved running performance.

8 Ways to improve running cadence

First, achieving a real improvement in cadence requires a consistent approach to training.

Second, there are several training approaches that are effective for improving cadence. Importantly, these approaches should be the staple of any endurance runner looking to improve their running speed.

So, rather than focusing specifically on increasing running cadence, use a multitude of different training methods that will help to improve your running. This will elevate your cadence to a higher level. But more importantly, you will become a faster runner.

With that in mind: here’s 8 training tips that will improve your cadence, stride length and running speed.

#1 Use hill repeats

Hill repeats are a great way to improve running speed. And when done correctly, they benefit both running cadence and stride length.

Why is hill training so effective?

First, when you run hills, you apply more force per foot strike, which is a great way to develop stride length.

Second, by running the hills at a high intensity, you also develop cadence. To do this effectively, we need to ensure that: 1) the hill isn’t too long; and, 2) it isn’t too steep – read more about the best gradients for hill sprints.

Short hill repeats and hill sprint workouts can be really effective.

#2 Include lactate threshold training

While hill repeats can push the upper limits of running cadence; lactate threshold training improves your ability to sustain a fast cadence and good stride length over prolonged periods. Importantly, these workouts help you develop the muscular endurance required to maintain run cadence.

Example sessions include:

- 25-30minute tempo run

- 2-3 x 10 minutes at threshold pace,

- or 2 x 15-20 minutes at half marathon pace.

You can see some examples of these within the 10k advanced running training plan.

#3 Include faster running intervals

Including faster intervals (faster than race pace) are also really beneficial. So why include these? By running at faster than race pace, you will become more efficient and find it easier to maintain a good cadence during your target race distance.

Overtime this leads to improvements in efficiency, cadence, and stride length.

As an example, if your focus is on 10k running, you could add in some 10k pace running intervals and run these slightly quicker than race pace.

You would also want to include some 5k, 3k pace and even some 1500m/mile pace intervals to develop cadence across a range of speeds.

#4 Short Sprints to Improve maximum run cadence

Working similarly to hill sprints, these are great way to improve maximal running speed. They’re also great for developing your maximum cadence and stride length. In effect, this will “pull-up” your normal cadence across a range of speeds.

How to include maximal sprints:

- One approach is to add in some short sprints before your weekly interval training workouts.

- This should actually improve your interval workouts as well.

- Examples include 4 x flying 30s (30m acceleration, 30m top speed, 30m deceleration), each separated by a couple of minutes of rest

- Another option is to include running strides, with the last 30-50m run at close to top speed.

- Speed endurance running intervals can also be very effective.

#5 Include running drills

Running drills improve neuromuscular coordination, technique, and your ability to apply force efficiently. Including the correct drills can be really beneficial for both cadence and stride length. They also help to improve ground contact time balance, which is important for running efficiency.

Two of the most effective running drills are high knees and A-skips.

High knee drills are particularly effective:

- Try adding in 3 sets of high knee running for 20-40m into your training schedule.

- Start at 20m and progress by 5m as your conditioning improves.

- Aim to include this 2-3 times per week – ideally before high-intensity training sessions.

Key points:

- Maintain a tall posture.

- Aim for a fast cadence.

- Knees should reach hip height (or above).

- Also, focus on a good arm drive.

- Don’t move forward too quickly – the focus is on a fast cadence, with high knee.

Progression: Run high knees on the spot for 20-30seconds.

#6 Don’t forget strength training

Strength training can improve your stride length and your ability to maintain a fast cadence, by improving muscular power, strength and muscular endurance.

An often overlooked area is Improving hip flexor strength, which is one reason hill running can be so effective.

Good strength training exercises include:

- Lunges

- Squats

- Straight leg deadlifts (single leg)

- Calf raises

#7 Maintain flexibility and mobility

Working on flexibility, so you can maintain a normal range of motion, is vital.

Why is this important? Put simply, a reduced range of motion limits stride length, whereas good flexibility allows for a longer stride length and a fast, efficient cadence.

A good approach is to ensure you include a dynamic warm up before training and work on mobility after training.

Another option is to set aside some time to work on mobility and flexibility – using a foam roller can be beneficial.

#8 Include longer runs

Including regular low-intensity endurance runs helps to improve muscular endurance, running efficiency and aerobic fitness.

Longer runs can be really useful, especially if you pay attention to when your cadence decreases.

It’s during these longer runs where cadence decreases when fatigue sets in – often, you need to take yourself to that point for an adaptation to take place.

So what do you do when cadence decreases? If you feel like your cadence is dropping during longer runs (a good indication is heavy foot strike), then try to focus on quick footsteps, with minimal ground contact time. By being aware that your foot strike is heavy, and focusing on quickly pulling your heel towards your glutes, you can decrease ground contact times and help to develop cadence. And by continuing to focus on maintaining cadence as fatigue sets in, you will improve muscular endurance and develop the specific endurance required to maintain cadence.

Overtime, these improvements will make it easier to maintain a higher cadence when running across a range of different speeds.

Key points

- Running performance is determined by your ability to run at a fast cadence and good stride length.

- It’s linked to running efficiency, performance, and injury risk.

- Runners have an individual optimal cadence, which varies depending on the speed they are running.

- Increasing cadence may benefit less well-trained runners by improving efficiency, reducing over-striding and ground impact forces.

- This is less beneficial for well-trained runners, who are more likely to running in their optimal range.

- Rather than looking specifically to improve cadence, focus on improving running fitness (specifically using faster intervals, hill repeats, drills, and threshold runs).

References

- Adams D, Pozzi F, Willy RW, Carrol A, Zeni J. (2018) ALTERING CADENCE OR VERTICAL OSCILLATION DURING RUNNING: EFFECTS ON RUNNING RELATED INJURY FACTORS. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Aug;13(4):633-642.

- Lieberman DE, Warrener AG, Wang J, Castillo ER. (2015) Effects of stride frequency and foot position at landing on braking force, hip torque, impact peak force and the metabolic cost of running in humans. J Exp Biol. 2015 Nov;218(Pt 21):3406-14. doi: 10.1242/jeb.125500.

- van Oeveren BT, de Ruiter CJ, Beek PJ, van Dieën JH. (2017) Optimal stride frequencies in running at different speeds. PLoS One. 2017 Oct 23;12(10):e0184273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184273. eCollection 2017.

- de Ruiter CJ, Verdijk PW, Werker W, Zuidema MJ, de Haan A. (2014) Stride frequency in relation to oxygen consumption in experienced and novice runners. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(3):251-8. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2013.783627. Epub 2013 Apr 14.

- Tartaruga MP, Brisswalter J, Peyré-Tartaruga LA, Avila AO, Alberton CL, Coertjens M, Cadore EL, Tiggemann CL, Silva EM, Kruel LF. (2012) The relationship between running economy and biomechanical variables in distance runners. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2012 Sep;83(3):367-75.

- Heiderscheit BC, Chumanov ES, Michalski MP, Wille CM, Ryan MB. (2011). Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Feb;43(2):296-302. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ebedf4.